Victoria on Film

One thing I’d hoped to include in the book was a bunch of still photos from various movies shot in Victoria. Although I did put in descriptions of the movies, Hollywood wanted outrageous sums of cash to reprint the stills in a (hopefully) money-making book. This blog is a strictly nonprofit venture, however, so I figure it's OK to use the images here. All these films are at the Greater Victoria Public Library or Pic-A-Flic.

Commandos Strike At Dawn (1942)

Commandos Strike At Dawn (1942)

Saanich Inlet is a glacially overdeepened valley filled with salt water. It is, by definition, a fjord – which is why it became a location for this wartime propaganda piece starring Paul Muni, about a Norwegian fishing village that rises up against its Nazi occupiers. In this scene the Allies land on the beach at Bamberton. Apparently parts of the village constructed for the movie still stand near Hall’s boat yard at Goldstream.

Vixen! (1968)

Vixen! (1968)

Victorians will laugh their ass off during the opening to this X-rated classic, in which the Inner Harbour, the Parliament Buildings, and (here) the Empress hotel figure prominently. The rest of the movie, about a crazed nympho who seduces guests at a fishing lodge, ostensibly takes place in Canada. But how much of it was filmed here? I emailed Harrison Page, who played the draft dodger and now stars in the TV series JAG, and he set the record straight: “No, we did not film in Canada, we shot in Northern Calf. [California] for Canada.” So now you know.

Five Easy Pieces (1970)

Five Easy Pieces (1970)

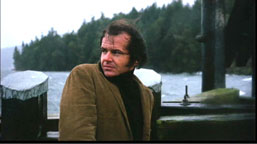

Victoria plays Jack Nicholson’s hometown in Washington State. Here he rides the Mill Bay ferry, the oldest continually operating route in B.C. Unfortunately, the mansion in Brentwood Bay that served as his family’s home, and the coffee shop and gas station on Highway 1 where he abandons Karen Black at the end of the film, have all been carelessly demolished. (Read that story here.)

Bird on a Wire (1989)

Bird on a Wire (1989)

In this romantic caper flick, Mel Gibson and Goldie Hawn are pursued by a motorcycle cop along Fisgard Street and up Fan Tan Alley. The scene makes the alley appear far longer than it is in reality, but shows it off to good effect. Bastion Square and the old Carnegie Library earn plenty of screen time too.

Little Women (1994)

Little Women (1994)

Winona Ryder strolls up a dirt-covered Humboldt Street to meet Gabriel Byrne, and her destiny. The Union Club is in the background, along with the lovely Belmont Building, which was constructed in 1913 out of reinforced concrete. It's named after the Belmont Saloon, which operated on the site in the 1870s.

X2: X-Men United (2003)

X2: X-Men United (2003)

The evil Stryker leads a helicopter assault on Professer Xavier's mutant training academy, played by Hatley Castle (the home of Royal Roads University). The castle is fencing off its grounds and will start charging $12 for tours this summer, so see the place now before you need a helicopter to get in without paying.

UPDATE (May 23, 2009): As a reader noted below, another made-in-Vic film is 1973’s Harry in Your Pocket, starring James Coburn, Walter Pidgeon, Michael Sarrazin and Trish Van Devere, about a team of pickpockets working around the Pacific Northwest. Last week, this hard-to-find flick finally turned up on Turner Classic Movies. Here’s a fun clip of the thieves hustling tourists in downtown Victoria:

If you want to see the whole movie, Modcinema has it on DVD.